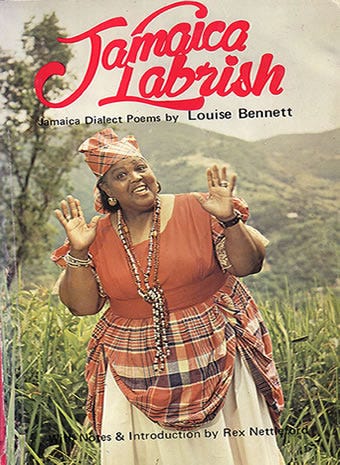

I have often told the story of growing up in my mother’s export business; of the hours in a storeroom full of hand sewn dolls, mahogany sculptures and the full, fresh smell of woven straw baskets everywhere. There were books too, in that back room of Xaymaca, named after what the original people called the island we lived on. Xaymaca, the land of wood and water, though by then there were no original people to speak of it. In that room , I memorized and recited the poems out of Louise Bennet’s “Jamaica Labrish”, written in the patois we never spoke at home but heard daily. Somewhere between language that had been lost and language that was imposed, was another kind of tongue; something from a land, not of wood and water, but sweetness and sweat. These were the words and lives collected and pressed into the pages by a woman I knew as Ms. Lou.

Louise Simone Bennett-Coverley, more commonly known as the character, Miss Lou, was a Jamaican poet, folklorist, writer, and educator. Bennet was in her mid 40’s by the time Jamaica was finally granted independence from Great Britain. By then she had she had been incorporating patois, the language of the laboring masses, into her creative writing and performance for over 20 years. In the years following 1972, that voice would be realized in form as Ms. Lou, Bennet’s witty, winking and culture defining creation.

While Louise was from a solidly middle class and educated Jamaican family, Ms. Lou was a working woman - a country woman – and savvy enough about the ways of the world to recognize inequity as global, historical, and constructed. For the newly liberated island republic, Miss Lou represented an evolving post-colonial identity, whose existence was both complex and creole. As one of Jamaica’s most influential figures at this time, Bennet is rightfully credited for using language to reimagine and reframe “Jamaican-ness”. Less discussed, however, is her full embrace of bandana fabric (also known as madras) as part of Ms. Lou’s iconic dress. Radical in its reconstruction of womanhood and nationhood in a moment of sheer possibility, the bandana now faces a dilemma in this new age…what does it mean to decolonize any artifact when that artifact is so deeply rooted in both colonialism and a post-colonial identity?

Traditional bandana is a loosely woven cotton textile produced almost exclusively in Chennai, India, formerly known as Madras. The textile we now know as bandana, or madras, began as a light, gauzy material prized by African and Middle Eastern merchants for its use in headpieces as early as the 12th century. When Dutch and then British traders arrived in India four centuries later, they would also recognize, and capitalize on the commercial opportunities of the textile. Originally imported to Great Britain in silk, madras was considered far too expensive for its colonial market. Demand for the material was so high, however, that British manufacturers would eventually copy the look in the cheaper cotton and sell that co-opted version to its West Indian colonies. Like an invasive species, this new transplant came to define the material landscape of the Caribbean.

Hand loomed madras in Chennai, India via Castaway Clothing

The story of bandana / madras in the Caribbean is, for all its transformation, an imperialist story, the mechanism and currency of a colonial economy. In this system, English laborers, British merchants, West African consumers, enslaved people throughout the “New World”, enslavers, landowners and free people were be inextricably bound together through the workings of cloth and clothing. What made Bennet’s use of banana particularly radical and progressive, was her confrontation of the colonial hierarchy, established and maintained through material signifiers such as textiles. She used language, performance, humor and clothing to engage and challenge the people of Jamaican to become Jamaican. Bennet’s work, and the work of countless individuals who formed and framed Caribbean identity through this textile, leaves us with the challenging question of our relationship to colonial material in an age of calls for decolonization.

In practice, decolonization is a calculated process of strategic engagement and diplomatic negotiation between colonial and anti-colonial forces. It is an epistemic disobedience that inevitably demands political change, economic independence, and cultural renegotiation. If colonization is an invasion and anti-colonialism is the defensive maneuver, decolonization might well ask, who are we who fight this war? Who were the crafts people whose trade and land were conscripted into this imperialist enterprise? What of the individuals who traded and were traded for a measure of cloth; the men and women for whom intimacy was bartered by the yard and the women who reclaimed a sense of self when belonging to oneself was rare? While decolonization has become a metaphorical catch phrase in popular culture, the true work of this movement is grounded in restoration and remembering.

From the Teodoro Vidal Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

There is an effort today to trend bandana towards something contemporary and fashionable. While I understand the impulse to do so, I continue to wrestle with the the disconnect between past and present implicit in doing so. Much like loaded words, bandana is heavy with history and meaning…should we expect it to be anything less? This desire to make bandana fresh, to purify madras in the baptismal waters of “fashion” is a false conviction and an unwarranted penance. In decolonization, Ms. Lou’s radical bandana may well have a second act, if only we grant it its full weight.

March Calendar Highlights

FULL CALENDAR AVAILABLE HERE

Lorraine O'Grady (American, born 1934). Rivers, First Draft: The Woman in White eats coconut and looks away from the action, 1982/2015. Digital chromogenic print from Kodachrome 35mm slides in 48 parts, 16 × 20 in. (40.64 × 50.8 cm). Edition of 8 + 2 AP. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York. © Lorraine O’Grady/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lorraine O'Grady, Virtual tour in ASL

Brooklyn Museum

Saturday, March 13, 2021

2–3:30 pm

Visitors from the D/deaf community are invited to experience our collection in an online American Sign Language (ASL) tour, led by a Deaf teaching artist. This virtual tour is in ASL only, without voice interpretation, and begins after a brief meet-and-greet. This month, dive deeply into the retrospective exhibition Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, and see how the artist advanced ideas in performance, conceptual, and feminist art.

Lorraine O’Grady is a New York-based interdisciplinary artist whose performances, photo and video installations, and writings locate timeless values in such topical issues as diaspora, hybridity, and black female subjectivity. At the same time, her work also politically shifts art discourse to show that such topics are not peripheral but central, that they profoundly shape global culture and contemporary art. The New York Times in 2006 called her “one of the most interesting American conceptual artists around.” Raised in Boston by Jamaican immigrant parents, O’Grady has said, “Wherever I stand, I must build a bridge to some other place.” O’Grady came to art late, after other careers; Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, her first public work, premiered when she was 45 and fully formed. This, combined with a hybrid upbringing, contributed to a critical distance on the art world and an eclectic attitude toward making art.

The program is free, but space is limited, and registration is required. Once you've registered, you will receive a secure Zoom link and password by email. This tour is designed for the d/Deaf community. If you're an ASL student, please email access@brooklynmuseum.org for more information about tours for ASL students.

Questions? Email us at access@brooklynmuseum.org or call 718.501.6520. Relay calls welcome.

Wicked Flesh Virtual Book Signing

w/ author Dr. Jessica M. Johnson

in conversation with Shivanee Ramlochan

If you missed the live event, see the recorded conversation here!

Dr. Jessica Marie Johnson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History at the Johns Hopkins University.Her work has appeared in Slavery & Abolition, The Black Scholar, Meridians: Feminism, Race and Transnationalism, American Quarterly, Social Text, The Journal of African American History, Debates in the Digital Humanities, Forum Journal, Bitch Magazine, Black Perspectives (AAIHS), Somatosphere and Post-Colonial Digital Humanities (DHPoco).

Purchase Wicked Flesh here

Discount Code: WICKED30-FM

Active through 2/21/21

Shivanee Ramlochan is a Trinidadian poet, arts reporter and book blogger. She is the Book Reviews Editor for Caribbean Beat Magazine. Shivanee also writes about books for the NGC Bocas Lit Fest, the Anglophone Caribbean's largest literary festival, as well as Paper Based Bookshop, Trinidad and Tobago's oldest independent Caribbean specialty bookseller. She is the deputy editor of The Caribbean Review of Books. Her first book of poems, Everyone Knows I Am a Haunting, was published by Peepal Tree Press on October 3rd, 2017 and was shortlisted for the 2018 Felix Dennis Award for best first collection.

Purchase Everyone Knows I am A Haunting here